Engaging Underrepresented Communities in Research

Attention to the unique inclusion and engagement needs of understudied populations is of critical importance to the advancement of genomic and precision medicine research, the elimination of health disparities, and an equitable distribution of the benefits generated by substantial, societal investment in these research areas. Common barriers to community participation in research can be overcome by enhancing participant trust in the research enterprise, building meaningful collaborations with research communities, and accommodating population-specific preferences for engagement, decision-making, return of results, data management, and results dissemination.

CERA interviewed researchers working on four projects focused on recruiting populations that are underrepresented in genomic and precision medicine research: adults with intellectual disability, older African Americans, Puerto Ricans, and North Kenyan pastoralists. These studies are fully or partially funded by the National Human Genome Institute (NHGRI). In the interview that follows, the researchers share their perspectives on recognizing barriers and facilitators of research participation for each community, building trust between researchers and community members, handling stigmatizing findings, and recognizing the need for special ethical considerations or safeguards.

Interviewees and Research Projects

CERA: What are some barriers to participating in research for the population you work with?

Susan Passmore: This is a complex and multifaceted problem for older African Americans. On the one hand, there is a history of research abuse that continues to make people hesitant to engage in research. The US Public Health Service syphilis study at Tuskegee is a prime example of abuse and there are many others. Overall, researchers have a long history of treating the suffering of some members of our society as justifiable in the pursuit of science. That history has consequences. There are also ongoing experiences of discrimination in health care settings and racism in our society that contribute to an understandable reluctance to be in a vulnerable circumstance. In research, we are asking people to take risks that history and context say are dangerous. This is not the whole story though. There are also other barriers originating from the research community that contribute to the overrepresentation of white participants. For example, there is some evidence that investigators and research staff may withhold opportunities to participate in research from people they feel will not make “good participants” (those that will successfully complete the requirements of a study). Scientists also have an ongoing tendency to privilege their own perspective on things like data access and the benefits and risks of research participation. This tendency can also present barriers to inclusive research.

Rebecca Siford, Carla Handley, Anne Stone, Sarah Mathew, Jason Scott Robert, & Melissa Wilson: North Kenyan pastoral populations have been marginalized socially, economically, politically, and educationally for a long time. These ethnic groups live in regions that are geographically remote from centralized infrastructure (e.g., roads, towns, schools, markets), which makes access by researchers and other outside entities challenging. Pastoralists migrate depending on resource availability for their livestock, which makes ongoing access by researchers difficult. Intermittent inter-ethnic tension and conflict also make the region potentially unsafe for researchers. Because the communities are remote and have limited exposure to formalized education systems which disseminate ideas about the significance and value of genetics research, they also have the potential to mistrust researchers external to the community who are collecting physical, genetic samples. For these reasons, long-standing interpersonal relationships between researchers and local communities—both before and after genetic sampling—are highly valuable. It is also good to offer ample time for sensitizing individuals to the significance of genomics research, the benefits and harms of participation, and potential downstream effects of the research, so that communities are equipped to decide whether participation is appropriate for them.

Timothy Dye: Puerto Ricans have experienced abuse from unethical research practices in the past, which often translates into their reluctance to participate. Puerto Rico is also a unique culture with a long, contentious relationship with the United States. Researchers are increasingly motivated to address the health issues of Latinx communities. However, in doing so, it is important to take the unique experiences of these communities into account.

Ivelisse Rivera: A sense of distrust can arise from a lack of project details. Researchers need to offer participants complete information about the research protocols before they can expect participants to commit to a participation decision.

Zahíra Quiñones Tavárez: Puerto Ricans are likely to report that they lack trust in government agencies and the healthcare system. As with other minority groups, lack of trust is a concerning barrier to participating in genetic and genomic research.

Nancy R. Cardona Cordero: It varies by generation or age group, but people tend to trust educational institutions, hospitals, and their doctors. Potential research participants need more information from researchers than they do from sources they already trust before they can engage.

Katherine McDonald & Maya Sabatello: Barriers to the participation of adults with intellectual disability in precision medicine research (PMR) are understudied. However, we can draw on knowledge derived from other areas of research with this population and one initial study of people with disabilities in PMR. These sources of information suggest that there are quite significant barriers including:

- a presumption by researchers that this population lacks the capacity to consent—a view that may prevent an invitation to participate;

- the information about how to participate in PMR studies is inaccessible;

- the presence of co-occurring, chronic health conditions can make it harder to participate or limit eligibility; and

- having difficulty communicating with researchers and feeling disrespected in these interactions.

These four barriers exist alongside other accessibility issues like challenges with transportation and inaccessible facilities. In addition, adults with intellectual disability may be discouraged from participating in PMR by family members or guardians (if they have these). These relationships with others can readily create additional barriers, including those linked to a lack of understanding of the benefits of research participation, perceptions that participation in research is too difficult, and worries about capacity to participate among family members and guardians.

CERA: What, if anything, would facilitate participation?

Susan Passmore: We need to listen the community to hear what they need from us. In my work, African American participants told us very plainly that the use of broad consent introduces a level of risk that is unacceptable for many. This makes sense given the history of research abuse experienced by this population, yet much of the research on the acceptability of broad consent has been done with white participants. African American participants told us that they were comfortable participating in studies using tiered consent models. The use of a biobank was not a problem. In fact, some specifically wanted their data to be available for other scientists, but the idea of broad consent introduced a lack of control over their biological samples that was a bridge too far. There is not a “one-size-fits-all” solution because different populations assess risk differently. If we are serious about diversity of research participation, then we need to face this fact and build studies that reflect our commitment. I’m not arguing that there needs to be a different study protocol for every group, only that we should be as inclusive as possible.

It’s a HUGE mistake to think that there’s nothing we can do to facilitate the participation of populations that are underrepresented in research. I understand feeling that way in the face of the justifiable distrust that is out there, but we can’t afford to give up. Not if we want to strive towards health equity. We need to change and that’s hard. Genomics research that is truly inclusive might not look like the studies that were conducted in the past. We need to keep scientific rigor, of course, but we can do a lot of bending and adapting in other ways. Thinking that nothing can be done ends the conversation and keeps us from striving for the solution.

Rebecca Siford, Carla Handley, Anne Stone, Sarah Mathew, Jason Scott Robert, & Melissa Wilson: The impetus to overcome barriers to community participation resides squarely with research teams and funding bodies. Work with remote and marginalized populations requires ample time and money for establishing a relational partnership with local communities (rather than a transactional relationship). A relational partnership is necessary for trust to be established and maintained between communities and researchers, for the dialogue between them to remain open, for the return of results to local people, and for the empowerment of local populations so that they can provide direction for future genomics research within their communities.

Timothy Dye: Creating a closer connection between researchers and communities would be helpful, so that there can be real dialogue—hence the name of our project, Diálogo Social Científico (DiSCo)! In Puerto Rico, being able to work fluently in Spanish or English, as the participants may prefer, is required. One of the best ways to increase the participation of Puerto Rican populations in genetic research would be to train more Puerto Rican scientists who are interested and supported in addressing the health needs of their communities. In places where the top priority is engagement with communities about their health priorities and research that could benefit them, we should support a vibrant and engaged network of Puerto Rican researcher communities of practice. This will take nurturing researchers from an early age, beginning with exposure to STEM in school, support for training at the university level, and facilitation of their transition to professional researchers. Support Puerto Rican scientists!

Ivelisse Rivera: It is important to steer away from jargon when offering information and promoting research sponsored by trustworthy institutions, not Big Pharma or others interested in commercial gain.

Zahíra Quiñones Tavárez: Actively and purposefully engaging communities is a crucial step in the design of strategies and interventions that will encourage greater participation in genetic and genomic research.

Leidymee Medina De Jesús: It is important to create a direct alliance between researchers and communities. To achieve this, there must be transparent, informative, and genuine communication from the beginning. It is vital that the community feel part of the research and can understand how essential their contribution and participation in it is. Similarly, researchers must create a respectful environment where the community feels safe and comfortable when expressing themselves and the researcher can listen and answer all their doubts or concerns. Researchers must practice empathy and sensitivity even more when dealing with a population that has been traumatized by unethical research practices.

Katherine McDonald & Maya Sabatello: Studies indicate that the most important supports for the inclusion of adults with intellectual disability are respect and treatment as equally contributing members of society. Therefore, a first initial step is making sure that adults with intellectual disability are invited to participate in PMR studies and feel welcomed when they do. This requires training researchers about the value of presuming competency, building in accessibility, and providing accommodations, and implementing measures to address the biases researchers may have about this population. Studies indicate that knowledge of these issues and built-in accessibility measures and accommodations are currently limited. Meaningful relationships between researchers and this community can also enhance trust and mutual understanding. Creating study materials—including consent forms and other information—that are accessible for this population is also critical on a practical level. These materials do not currently exist.

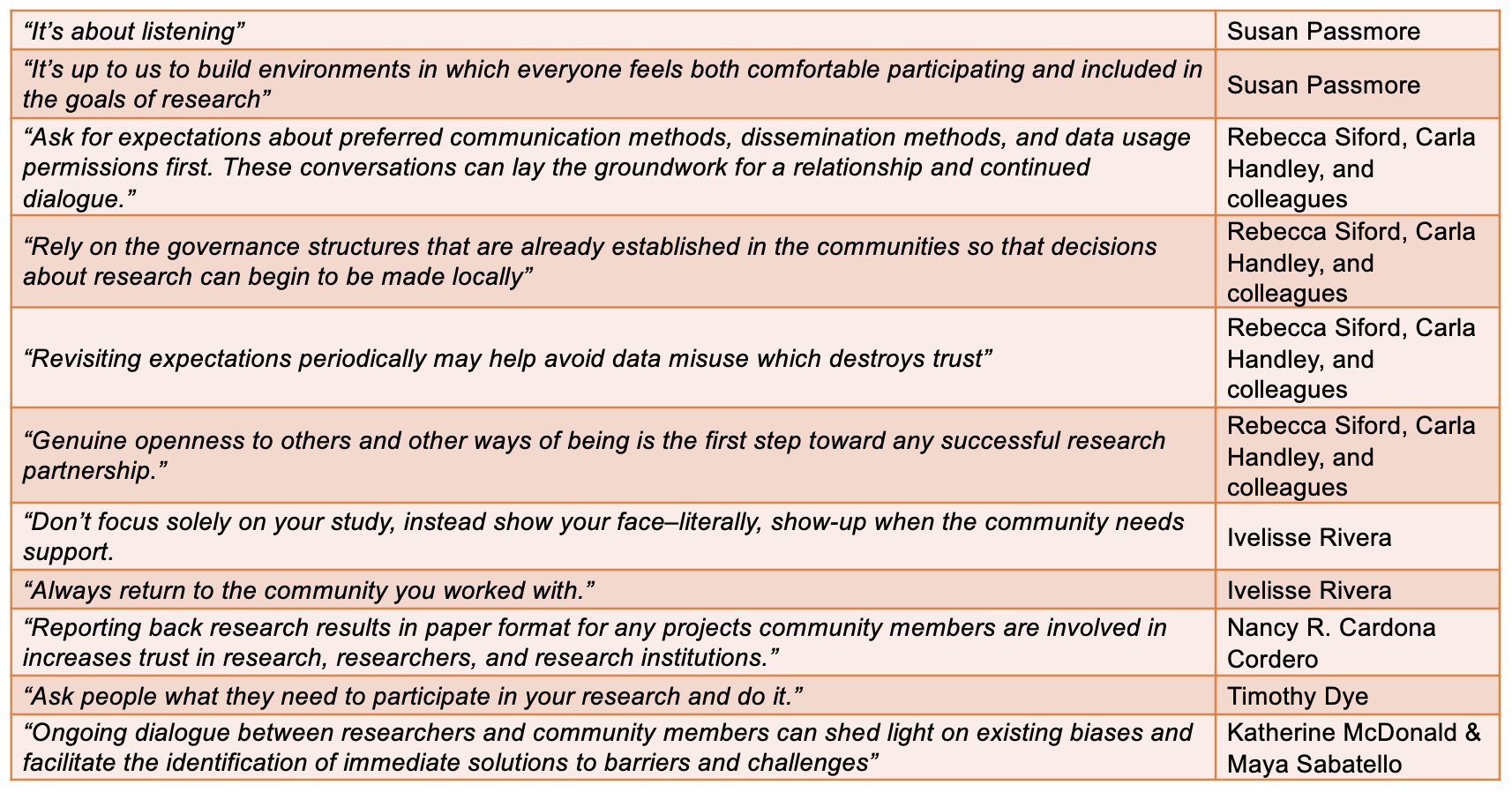

CERA: How can we build trust between researchers and underrepresented populations, especially for communities where that trust has been tested or broken?

Susan Passmore: It’s about listening. We need to be in this work together with communities that have justifiable reasons for distrust. Most people want to participate in research for altruistic reasons, but they also want to be sure that researchers are working toward that same goal. It’s up to us to build environments in which everyone feels both comfortable participating and included in the goals of research.

Rebecca Siford, Carla Handley, Anne Stone, Sarah Mathew, Jason Scott Robert, & Melissa Wilson: Trust was developed during our previous work—with the community expectation that the relationship would be sustained by continuous communication over time. Community members from Rendille and Turkana have expressed trust in members of our research team because they have returned multiple times, have communicated in their absences, provided assistance or education, and brought back results from previous studies.

Part of our current work explores the expectations community members have for researchers and governance of genetic data. This work suggests it is important to ask for expectations about preferred communication methods, dissemination methods, and data usage permissions first. These conversations can lay the groundwork for a relationship and continued dialogue. We also recommend relying on the governance structures that are already established in the communities so that decisions about research can begin to be made locally. Community expectations and participation in the research process should be expected to fluctuate as exposure to genetics research becomes more normalized. Revisiting expectations periodically may help avoid data misuse, which destroys trust. When we have asked how other researchers can develop a trust-based relationship, community sentiments commonly focus on repetitive behavior, including seeing researchers continuously follow through on their promises. Overall, we recommend determining expectations and communicating frequently about the research process.

It is critical to learn as much as possible about your research community, their culture, and governance structures, as a collaborative relationship is being built. It is also especially important to avoid making assumptions based on the researchers’ own backgrounds. Genuine openness to others and other ways of being is the first step toward any successful research partnership.

Timothy Dye: True commitment and engagement would help! People know when you are truly committed. They need to see researchers not just recruiting participants for a study, but also see them in other aspects of life expressing respect and admiration for the communities where they are recruiting. Puerto Rico routinely experiences environment-related disasters. Researchers and their teams can help with relief efforts, volunteer in some way, and be present. Finding ways to truly listen to community concerns and to involve community members before the study is fully developed is also important. Very often, people want something back from the researchers, whether it is their own results, the results of the study, or, at the very least, sincere acknowledgement of their contribution.

In my work with communities that have mistreatment and abuse by scientists in their history, I find it fascinating that people are still quite supportive of research participation. No one wants to be exploited. The altruistic nature of people in communities that may have experienced abuse in the past should be highly valued and respected by scientists. Ask people what they need to participate in your research and do it. Set up a project so that you and your team are accountable to the people in your study and honor their participation for the gift that it is.

Zahíra Quiñones Tavárez: It is important to design strategies based on the principles of community participatory research and community engagement, for example, establishing shared decision making and engaging researchers from Puerto Rico at the outset.

Ivelisse Rivera: Involve the community! Incorporate a community advisory board into your research structure and allow input from community members to drive promotion and recruitment efforts. Don’t focus solely on your study, instead show your face–literally, show-up when the community needs support.

Always return to the community you worked with. People have said, “Someone did a study here a few years back, but we never heard anything else.” Don’t ignore your participants. Return with a purpose: sharing of results, disaster relief, or a simple follow up visit to see how the community has thrived or evolved. If you continue to nurture those community connections, you have a higher chance of being respected and well-received in the future. As researchers, we must be committed to the people, not just to our data.

Nancy R. Cardona Cordero: We have learned that reporting back research results in paper format for any projects community members are involved in increases trust in research, researchers, and research institutions.

Katherine McDonald & Maya Sabatello: Community-engaged research has shown to be a useful process for building trust between researchers and underrepresented populations. Such engagement builds on bi-directional relationships, whereby both the researchers and community members are viewed as experts and equal partners throughout the research cycle—through conception, implementation, dissemination of results, and knowledge translation. The ongoing dialogue between these stakeholders can shed light on existing biases and facilitate the identification of immediate solutions to barriers and challenges (which demonstrates the commitment to inclusion in real time situations).

Recommendations for Building Trust

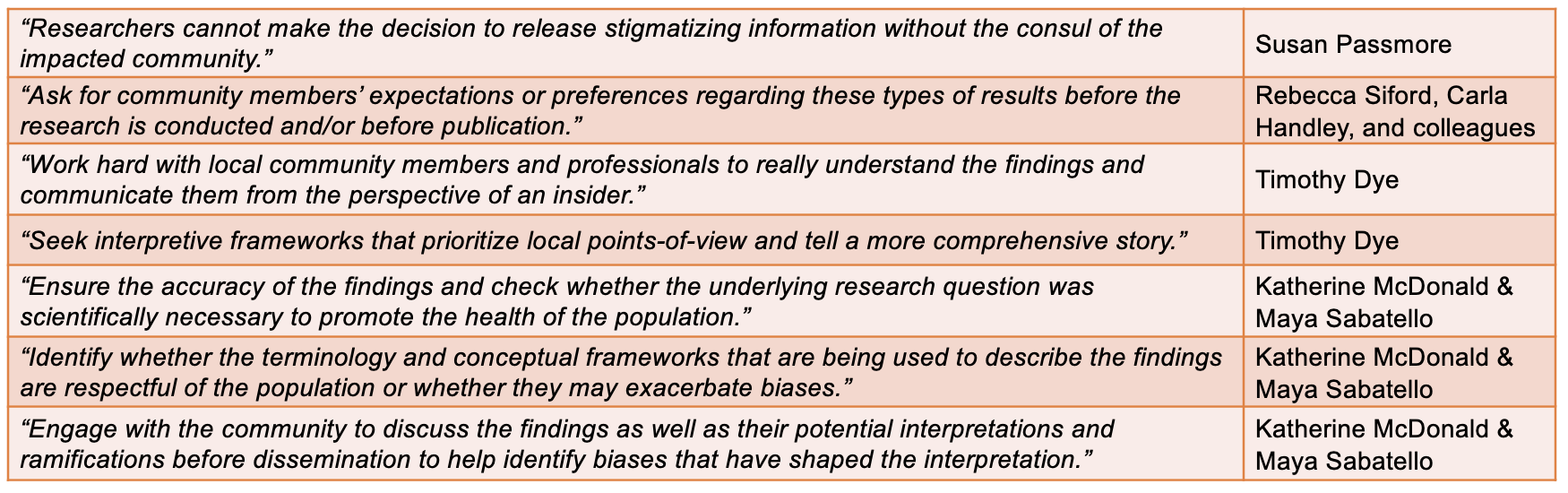

CERA: What recommendations do you have for researchers who may be handling findings that could stigmatize a population?

Susan Passmore: Researchers need to seriously consider the damage that they might cause to communities. The pain of stigmatization is real and sharply felt. Moreover, it does not just have an impact in a limited group of people. The reverberations are felt through communities, potentially, for generations. Researchers that inflict harm damage the relationships of those communities to other researchers and institutions. They may cause communities to be hesitant to participate in research in the future and, in turn, exacerbate existing health disparities.

The decision to release stigmatizing findings should be informed by the relative scientific importance of the findings. We are not under an obligation to publish everything we find. Harm should be balanced against the potential to help others. Having said that, I will quickly add that the scientific community cannot be the sole judge of the worth of findings or the harm to communities. Researchers, in fact, cannot make the decision to release stigmatizing information without the consul of the impacted community. Our perspectives on such matters are just that, “our perspectives.” The community has their perspectives. We should all be sharply and continuously aware of the weaknesses of “it’s for the betterment of science or society” arguments, and the negative consequences that have followed these arguments in the past.

Rebecca Siford, Carla Handley, Anne Stone, Sarah Mathew, Jason Scott Robert, & Melissa Wilson: Accidental findings in genetics research are not uncommon. Our recommendation is simply to ask for community members’ expectations or preferences regarding these types of results before the research is conducted and/or before publication. Currently, publishing without consultation is the standard, but we are finding that participants and in genetic research and other community members in northern Kenya are interested in hearing results before publication and want to be consulted if the results are contrary to what they know about themselves. We use a series of questions to elicit community preferences:

- What do you think future DNA research should not study about your people?

- In general, do you want to hear about the results of a study before we share in books and on the computer or can we come and share after?

- If a DNA study shows a result that conflicts with something you know to be true about your community, do you want us to tell you about this result or should we keep it to ourselves?

- If a DNA study shows a result that conflicts with something you know to be true about your community, can we share the information with others in books? Or, do we need to ask first before sharing in books?

Timothy Dye: Work hard with local community members and professionals to really understand the findings and communicate them from the perspective of an insider. Seek interpretive frameworks that prioritize local points-of-view and tell a more comprehensive story. Research should not damage a community. Do no harm!

Katherine McDonald & Maya Sabatello: When findings may be stigmatizing for a population, there are a few things that can be done. First, ensure the accuracy of the findings and check whether the underlying research question was scientifically necessary to promote the health of the population. Second, identify whether the terminology and conceptual frameworks that are being used to describe the findings are respectful of the population or whether they may exacerbate biases. Third, engage with the community to discuss the findings as well as their potential interpretations and ramifications before dissemination. This engagement can help identify biases that have shaped the interpretation of findings.

Recommendations for Handling Potentially Stigmatizing Findings

CERA: Has your work with this population suggested the need for any special ethical considerations or safeguards?

Susan Passmore: We need to be respectful of how risk is determined by different communities. This varies by experience, history, and cultural values, among other things. A researcher relying on their own estimation of risk or an estimation by people like themselves, is privileging one perspective and, potentially, disenfranchising others. This is a conflict with the ethical principle of justice which dictates that both the benefits and risks of research are fairly and equitably distributed.

Rebecca Siford, Carla Handley, Anne Stone, Sarah Mathew, Jason Scott Robert, & Melissa Wilson: A 2017 study by members of our research group explored how the Rendille, Samburu, Turkana, and Borana ethnic groups are genetically related. As part of the effort to return the results of the study to each group, Rebecca Siford is measuring the effectiveness of dissemination materials and asking both research participants and other community members about their expectations for genomics research. This experience has highlighted the need to create dissemination materials with input from local community members. Through trial and error, we found that generic images were poorly received, but images that we tailored to each specific population were easily digestible. We used beads to explain DNA by pairing the poster image with physical beads that the local women usually wear. Many community members request that results be returned, and updates provided during the research process for each future genetic study, whether conducted by local research assistants or outside researchers. This work has also revealed population-specific preferences about community compensation, consent, and governance (e.g., data usage permissions). We suggest that funding agencies make small grants available for returning results at several stages during the funded period of the study and afterward. Researchers should consider community preferences when designing and returning the results of research with these communities. IRBs/ERCs should also consider these preferences.

Timothy Dye: Our project is organized around the ethical concept of distributive justice. Puerto Ricans have the right to participate in ethical research that could benefit them and their community. To exclude them systematically, or not address their needs, is to deny them the potential benefits of research that could address their priorities. Puerto Ricans are a unique culture—it's not always accurate to extrapolate findings from a study with another population to theirs. Respect and communication are crucial components of work with communities to design and implement research that they feel is appropriate to enable their participation.

Ivelisse Rivera: It is important to offer this population the courtesy and respect of not lumping them in with all Latinx groups. They are a unique culture with strong island ties that surpass generations (including its diaspora). For this reason, it is important to intentionally create all materials in both English and Spanish.

Katherine McDonald & Maya Sabatello: There are many considerations, including those shared with the broader disability community and other minoritized populations, and some unique ones. On the former, there is a clear need for disability ethics that calls for accessibility and accommodations in all research studies, including time for research participants to engage in research activities at a comfortable pace. On the latter, the need for cognitive accessibility and thoughtful attention to built-in supports for decision-making about research participation are essential. This may include offering one-on-one support (e.g., reading survey items aloud, providing support for recording answers, etc.), having open conversations about the accommodation of individual support requests, and enhancing the assent process when someone has a guardian.

CERA: What strategies, if any, do you use to ensure that community members are meaningfully involved in your own research?

Susan Passmore: Working with community advisory boards and with community-based organizations are two of the most popular ways. Researchers can also explore community perspectives on their studies using social science research methods. This is one of the benefits of team science. One of the changes that might be necessary is investment in a more rigorous approach to recruitment science. For my part, I use simple methodologies that enable research teams to explore participant perspectives quickly and effectively, and then allow those results to shape inclusive research design and study protocols.

Rebecca Siford, Carla Handley, Anne Stone, Sarah Mathew, Jason Scott Robert, & Melissa Wilson: North Kenyan pastoralist participation has been at the heart of our research since team members began working with these communities in 2004. We hope to support an agenda that moves local research from simple, community-based participatory research, to community-led research, and ultimately, to community-initiated research programs. We have spent years living alongside pastoral populations throughout northern Kenya, endeavoring to understand local values, beliefs, motivations, and customs as they relate to research agendas. We have employed field assistants from within local populations and supported their personal growth, educational development, and increased autonomy in conducting research among their communities. We have developed research and educational materials in tandem with community members that reflect culturally meaningful touchstones and respect sensitivities. Our current ELSI project is supporting the establishment of local research committees or platforms for ongoing dialogue between local people and the research community. The committees will be a place where research projects can be discussed and approved by the community, advice can be solicited, issues can be raised, and research results shared. These activities will make local communities into equal partners in the production, dissemination, and benefits of genomics research.

Timothy Dye: We have a community advisory board with representatives from different communities throughout the country. Qualitative research is the basis for all our projects, and it helps us learn more from community members themselves. We also engage with neighborhood groups, health centers, educational programs, and other researchers. This engagement helps us to be as aware as we can be about local perspectives and needs.

Zahíra Quiñones Tavárez: It is important to address the needs of the communities along with your research agenda and involve community members, stakeholders, and researchers in every stage of the project.

Ivelisse Rivera: Involve community members from your target population in all aspects of your research plan, both pre- and post-implementation.

Nancy R. Cardona Cordero: It is important to create partnerships with community-based organizations or leaders.

Katherine McDonald & Maya Sabatello: The best strategy to ensure that community members are meaningfully involved in the research is to engage with individuals with lived experience throughout the research project. Including them as members of the research team and consulting them on all aspects of the study and study material are critical. Engaging with organizations that represent the community is also invaluable for ensuring participant engagement with the study and researcher sensitivity to the needs and views of the population. This could be done through regular meetings, webinars, and other interactions. Critically, we must also create accessible environments to support engagement. This may involve re-imagining meeting structures, integrating multi-modal communication, prioritizing plain language, and establishing dynamics that enable input and are receptive to the perspectives of those with lived experience of disability. These accessible environments can enable community members to truly influence the understanding of researchers and study decisions.

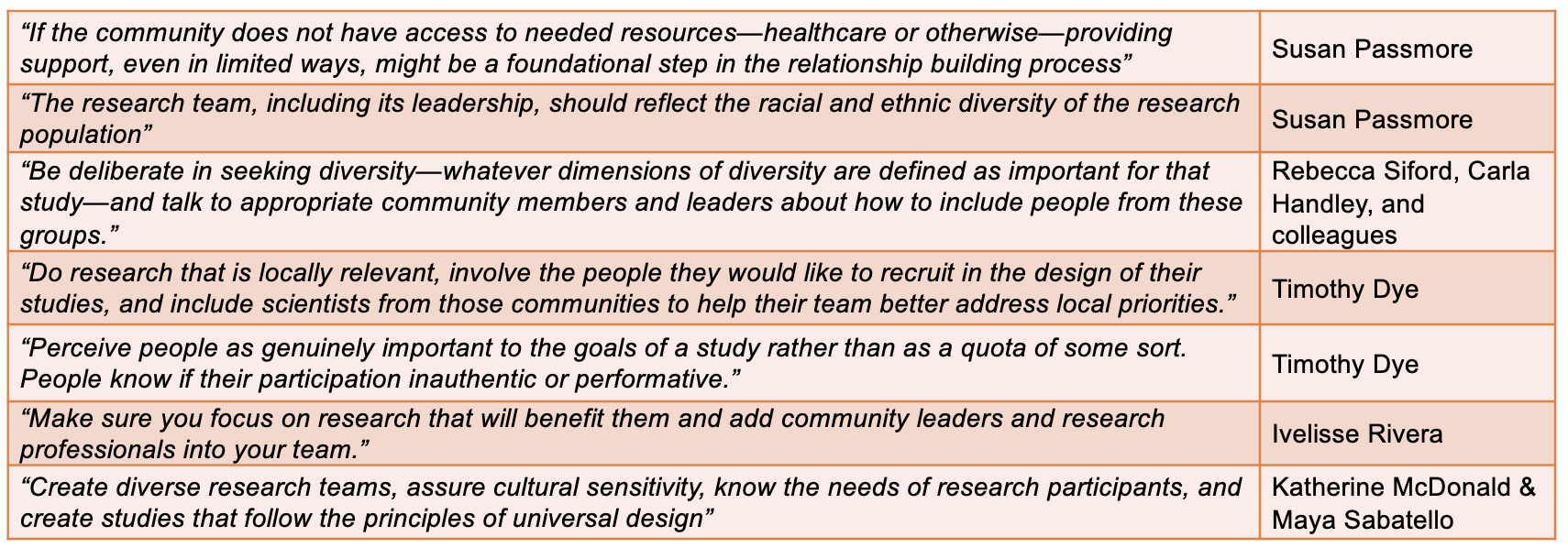

Recommendations for Recruiting Diverse Participants

CERA: What advice would you give to researchers who would like to recruit diverse participants?

Susan Passmore: We are at a place requiring some thoughtfulness and innovation. We cannot rely on the traditional ways of approaching recruitment or retention in research. Those old ways have not successfully worked to increase diversity of research participation or move us substantially closer to health equity. In addition to the strategies I have mentioned already, research teams need to demonstrate trustworthiness and their respect for underrepresented communities by considering their circumstances and needs. For example, if the community does not have access to needed resources—healthcare or otherwise—providing that support, even in limited ways, might be a foundational step in the relationship-building process. The research team, including its leadership, should reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of the research population. People notice when the team excludes people that may identify like them. They may wonder why, conclude that diversity is not a true value of the team, and be hesitant to participate.

Rebecca Siford, Carla Handley, Anne Stone, Sarah Mathew, Jason Scott Robert, & Melissa Wilson: Overcoming barriers to participation resides squarely with the research teams. Our target demographic is defined across ethnic groups, then within clans, and further subdivided across sex, age, and participation status in the 2017 study linked above. It is important to be deliberate in seeking diversity—whatever dimensions of diversity are defined as important for that study—and talk to appropriate community members and leaders about how to include people from these groups.

Timothy Dye: Researchers should do research that is locally relevant, involve the people they would like to recruit in the design of their studies, and include scientists from those communities to help their team better address local priorities. It's important to perceive people as genuinely important to the goals of a study rather than as a quota of some sort. People know if their participation inauthentic or performative. Be authentic and care as much for the people participating in a study as you do for the study itself!

Zahíra Quiñones Tavárez: It is important to be transparent, show your face, and talk to people within communities. Researchers should also identify, engage, work with, and answer the questions of community leaders.

Ivelisse Rivera: Don’t be afraid to approach these communities. Take your time to learn from them and about them. Make sure you focus on research that will benefit them and add community leaders and research professionals into your team. Working with direct input from your target population makes a difference.

Katherine McDonald & Maya Sabatello: Researchers should commit to diverse inclusion from the get-go! This includes creating diverse research teams, assuring cultural sensitivity, knowing the needs of research participants, and creating studies that follow the principles of universal design (accessible to people with diverse abilities). This can also include partnering with researchers with disabilities, those with experience facilitating the inclusion of adults with intellectual disability, and other people with disabilities in research.